Miss Sophia: Digital Tent-Making

In her living room, Sophia unfolded a yellow tent beside the kitchen table she called her only space. Once a broadcaster in South Korea, she began filming on YouTube after immigrating, shaping digital diaries late at night. Between motherhood and vulnerability, the yellow tent mirrored her channel: a quiet act of presence and self-expression, softly declaring, “I am here.”

It was a sunlit afternoon when I carried the yellow carry on into Sophia’s apartment. She greeted me warmly in a short sleeved T shirt and green leggings, her socks white against the hardwood floor. In an earlier conversation she had decided to set up the tent beside the kitchen table, the only space in the home she claimed as truly her own. The apartment, shared with her partner and two young children, carried the rhythms of family life. Children’s drawings and collages covered the walls, board games and trains rested across the carpet, and shelves overflowed with Korean and English books.

She offered me a cream filled Korean cake bought from a nearby market, and I gave her a Taiwanese sesame snack in return. Light poured gently through the second floor windows and the hum of lawn mowers outside blended with the quiet pulse of suburban air. Sophia explained that the afternoon was her rare moment of solitude, before her children returned home. When the tent began to take shape in the living room, she gasped with joy. “Wow,” she exclaimed, her eyes wide. Sunlight streamed through the sliding door, glowing against the yellow fabric. The tent was more than cloth and poles. It opened into a feminist space of self representation and memory making.

When I invited her to bring something meaningful into the tent, she paused. “Would it be an object. I have a YouTube channel that is very meaningful to me.” She disappeared into the bedroom and returned with an iPad. Inside the tent she showed me her channel. I listened as she shared the story behind it. In South Korea she had worked in broadcasting, but upon immigrating she suspended her career to follow her family. With no legal authorization to work and two small children, she struggled. “I felt gloomy and frustrated,” she said. “I felt useless.” The weight of isolation, language barriers, and the unfamiliar demands of American motherhood pressed against her. At one point she wanted to leave, but for the sake of her family she chose to remain. Out of this heaviness came her decision to create “something meaningful for myself.” She began filming.

At first the videos were simple diaries, shared only with relatives in Korea. She filmed with her phone, edited on the same device, and uploaded late at night when the household slept. “Every night, after my children and husband go to sleep, I sit alone to edit. That is my time.” Over three years she created more than two hundred episodes. They recorded her preparing kimbap, visiting local parks, attending school events. The channel became not only a thread to her past but a lifeline for the present. Other immigrant women found her online. One became a close friend. She laughed. “I used to care about followers. After five hundred, I let that go. I just wanted to make a pile of memories for myself.”

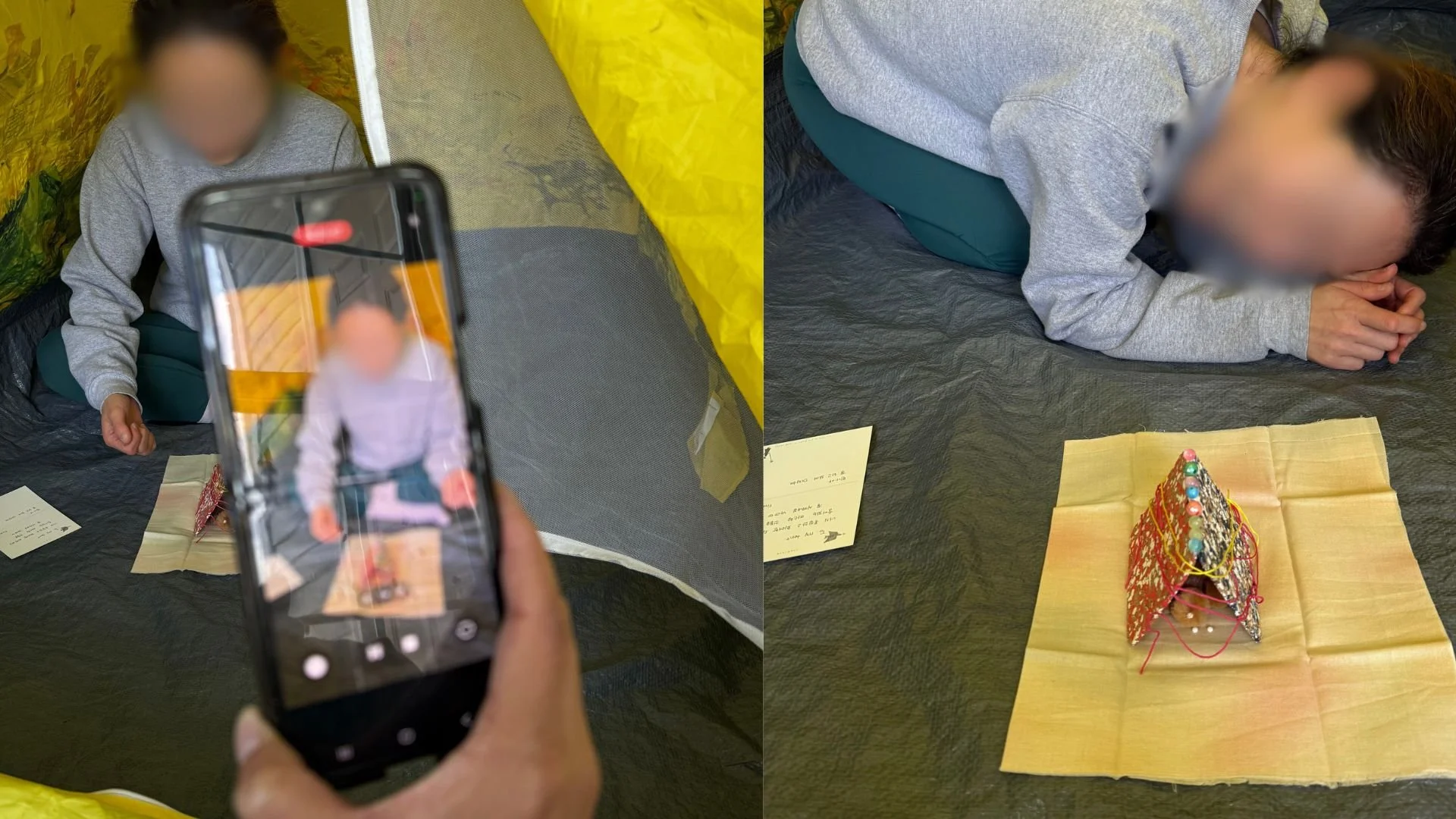

Inside the tent I suggested she film the process for her channel. She grew excited. “Can I video your yellow tent.” Together we adjusted angles, positioned materials, and filmed our collaboration. The tent stretched into digital space, becoming part of her online diary, refracting our co making into community. It was no longer just a physical structure. It was entangled with her virtual archive, alive as a feminist space of co-presence and mutual witnessing.

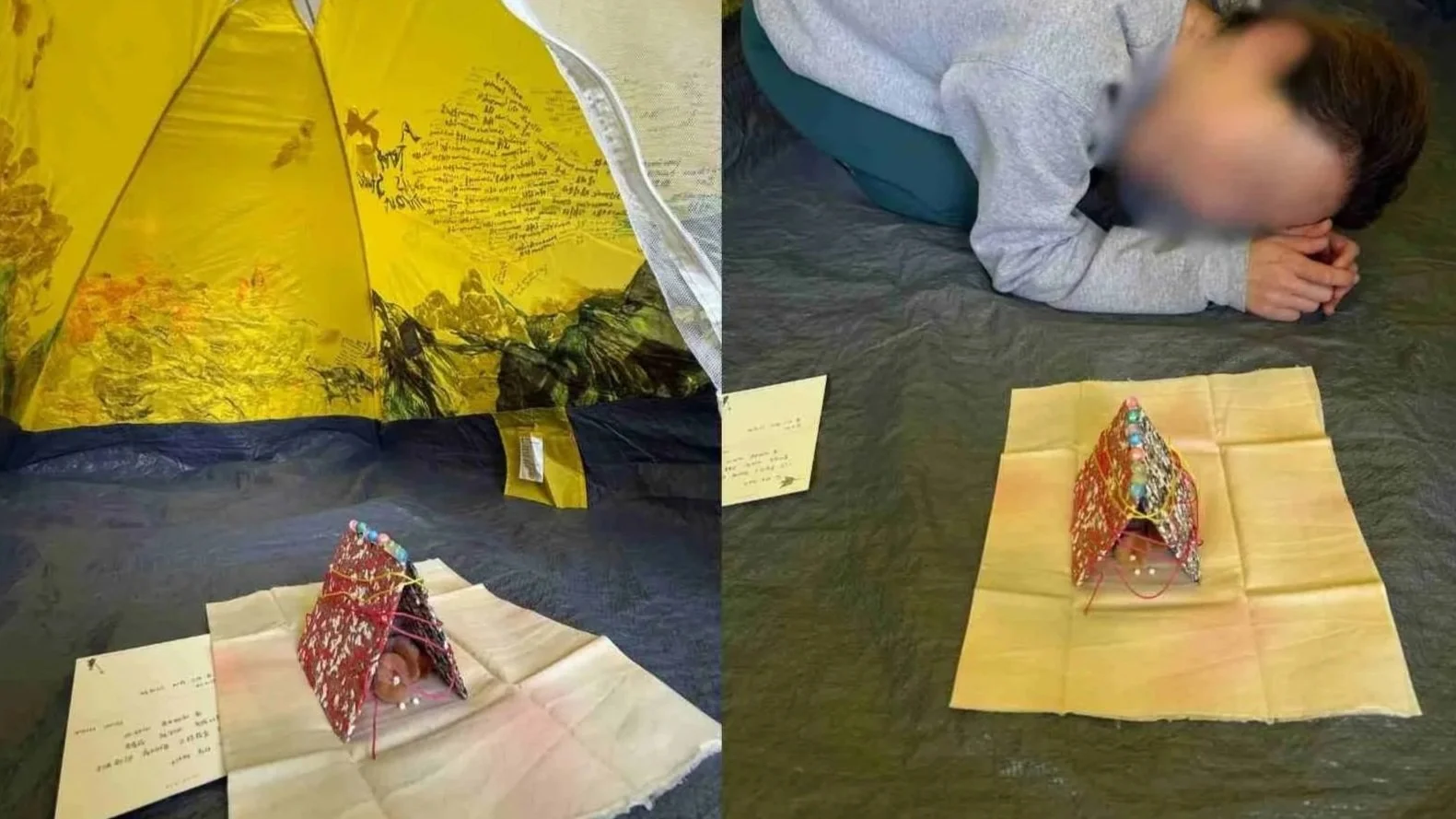

Sophia then made a small tent of her own. She chose soft textures and pastel pom poms. “This yellow means something to me,” she said. “I want people around me to be kind and flexible, like this texture.” She placed the pom poms inside. “This is me. People think I am outgoing, active, maybe glamorous. But actually, I am soft. I get hurt easily. I pretend to be happy, but only a few people know how I really feel.”

Her tent carried the duality of visibility and vulnerability. The outside was bright, decorated, resembling the cheerful life shown in her videos. Inside she admitted to quietness, longing for her own time. “The videos are my diary. My way to say, I am here.” The process of tent making surfaced hidden tensions, much like her channel.

One story weighed heavily on her. Her three year old daughter, once fluent in Korean, struggled in preschool. She cried each day, unable to understand English, and longed for classmates with blond hair and blue eyes. Sophia repeated her daughter’s question. “She asked me, I can speak a little English now. Is my hair turning blonde and my eyes turning blue like American children.” Sophia’s voice trembled as she recalled the moment. The tent held the ache of that memory. Her daughter’s wish for transformation revealed the racialized ideals she already faced. Sophia, as an immigrant mother, felt powerless yet deeply connected to her child’s pain.

Sophia also spoke of her own insecurities. “I met American, real American. I feel nervous. I do not know why.” Although her English flowed easily, she described feelings of fear, embarrassment, even shame when speaking to native speakers. Her words reflected how linguistic tension lingers not only in fluency but in the embodied hierarchies of who is heard, who is foreign, who belongs.

When she finished her small tent, I invited her to write a letter to it. She wrote in Korean, folded the note, and tucked it inside. “I hope your splendid appearance can protect your warm and soft inside,” she wrote. Afterward she reflected, “Before making it, I kept asking, who am I. But after finishing, I realized this is me. I feel more comfortable. I love myself more.”

Sophia’s tent stood in the living room, gentle with color, soft with pom poms, glowing beside the yellow structure we built together. It carried her digital diaries, her maternal anxieties, her quiet resilience. Her tent, like her channel, was a diary of presence, both fragile and luminous. In it she found a way to speak across distance and silence, to say: I am here.