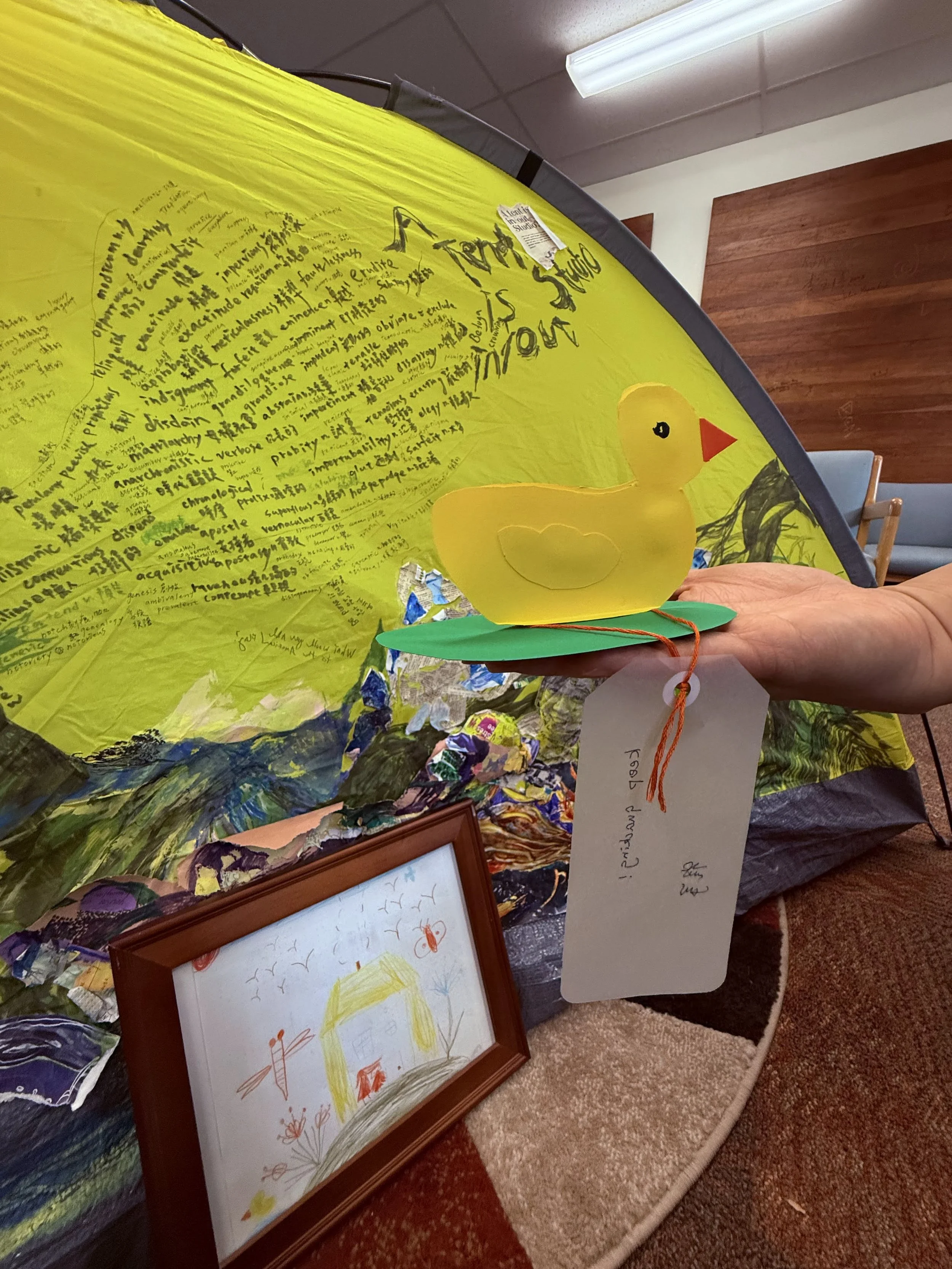

Keep Quacking:

A Yellow Duck Tent Story of Immigrant Mothering

In a university classroom, Ki closed the yellow tent carrying transition. She traced and cut the outline of a duck from her daughter’s drawing, shaping paper into a fragile yet steadfast tent. Folding, erasing, and redrawing, she built a shelter of memory and resilience. Within its bright body she placed an amulet that whispered a quiet vow of survival: keep quacking, keep going, keep heard.

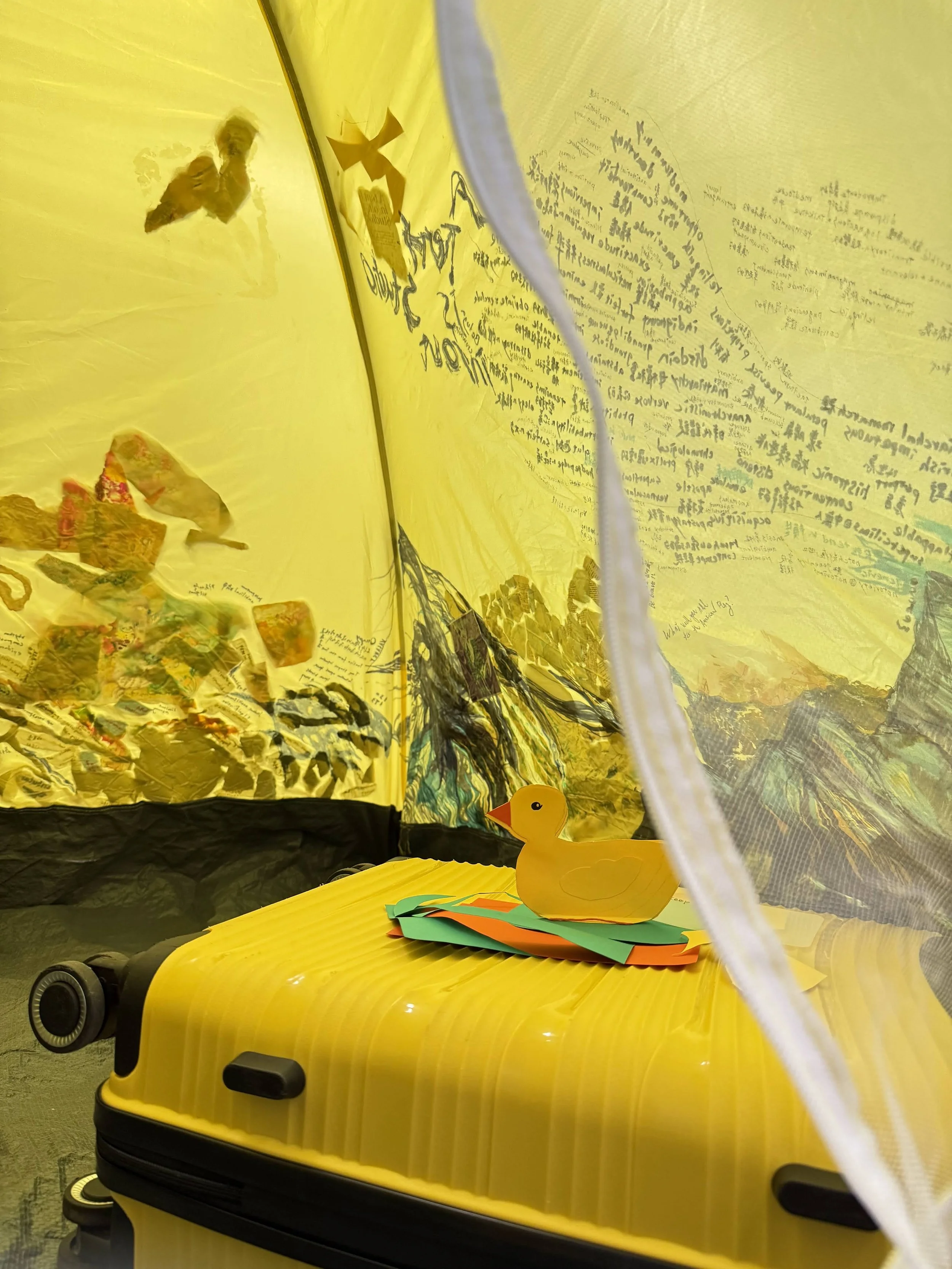

Ki entered a quiet university classroom accompanied by a friend who had traveled from New York for her PhD commencement. The moment should have been one of celebration, yet it carried another weight. She had just been laid off, and the future opened as both possibility and void. The joy of completing her doctoral journey pressed against the anxiety of unemployment and the everyday demands of raising three children in an interracial family. She longed for a pause, a shelter where she could gather her scattered energies. She chose the classroom deliberately. It was a place she knew, a space shaped by years of study and survival, a place removed from domestic tensions.

When the yellow tent rose in the room, Ki’s body seemed to soften. We began speaking in Mandarin, her northern cadence folding into my Taiwanese inflections. Sometimes English slipped through, reminding us of the constant negotiations of language. I mentioned how tent and tension share a root. She smiled, then her eyes dimmed. The word carried her to a memory she had not intended to revisit.

She told me about her daughter’s first school exam in the United States. A pediatrician had ordered extra tests, expensive and unexpected. When Ki asked why, the reply came bluntly. Because you come from China. The doctor recalled traveling to China in the late 1980s, describing the country as dirty and chaotic. That memory had hardened into a professional judgment decades later. Ki was left with bills, but heavier still was the feeling of being distrusted, of having her child defined by nation rather than need.

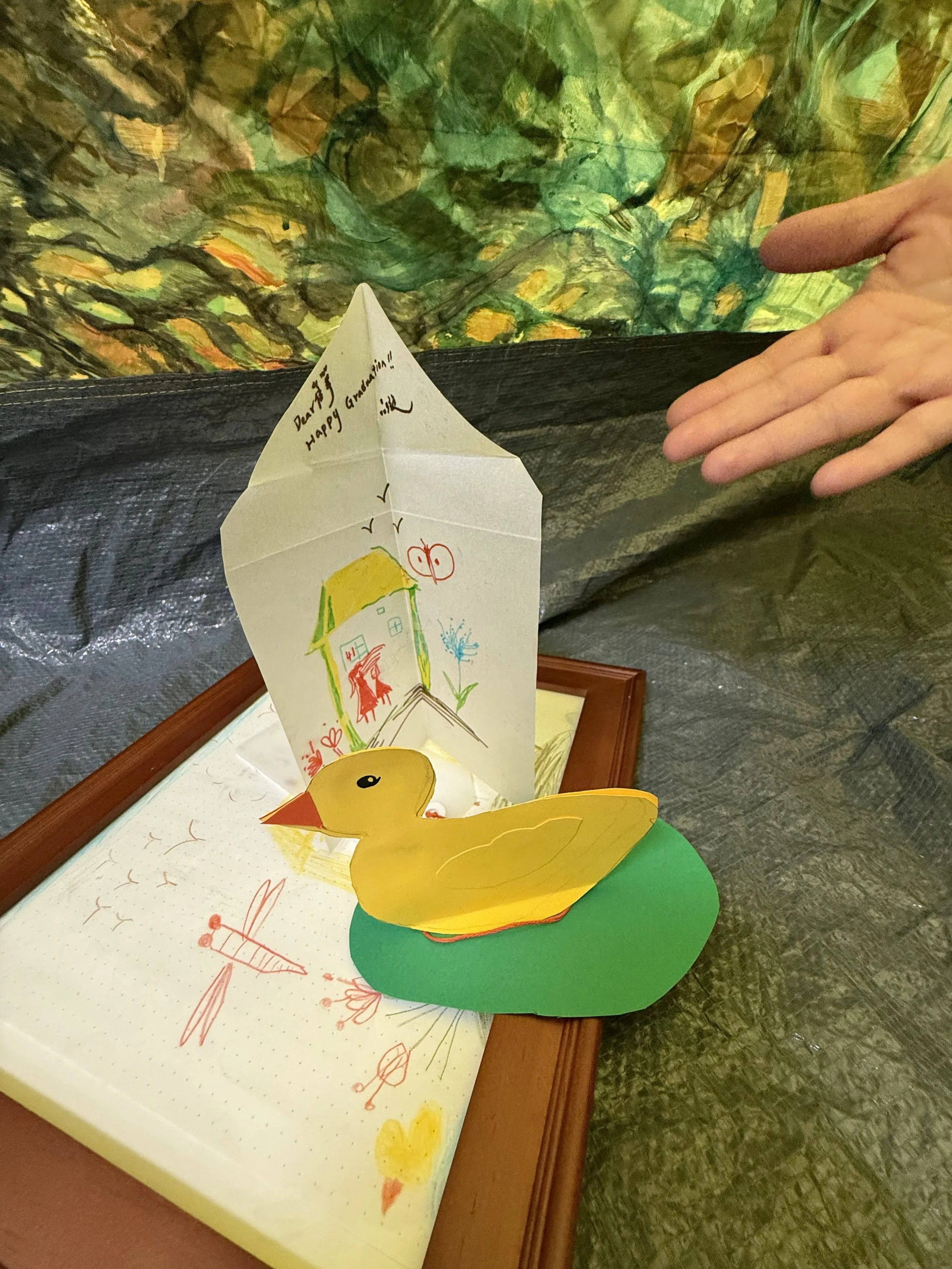

From her bag she drew a wooden frame. Inside was a drawing made by her daughter on the airplane when they left China. The child had been five, restless and not yet verbal because of special needs. Ki had packed colored pencils and paper, hoping to calm her. The drawing showed a house, flowers, the sun, an airplane, and in the corner, a yellow duck. Over the years that duck returned again and again in her daughter’s sketches. It became a small companion, a sign of presence without words. Ki touched the frame. “She could not speak then,” she said, “but she drew a lot.”

In the yellow tent, inspired by that memory, Ki decided to make a yellow duck of her own. She tore a sheet of yellow paper, laid it on the table, and began to trace. The pencil moved slowly. She drew the curve of the head, erased, tried again, adjusted the beak, smoothed the line of the back. Each attempt brought her closer to her daughter’s image. When satisfied, she cut the outline carefully, scissors whispering through the paper. She colored an eye with black ink, bold and round. To give the form depth, she cut a second duck, joining the two with a green base so they stood upright, facing one another, creating a space in between. Into the hollow of the neck she tied a small amulet on which she wrote three words: keep quacking.

The process was quiet but filled with meaning. Tracing, erasing, cutting, folding—each gesture carried her memories forward. The duck stood fragile, yet it radiated persistence. In its body of paper Ki placed her grief and her strength. She spoke of childbirth, of taking a taxi alone to the hospital in China and announcing calmly, I am here to give birth. She laughed with embarrassment at how she once tried to write an essay about that moment only to lose the file, as if memory itself had escaped her grasp. Her friend listened closely, adding her own story of pregnancy and recovery. In the yellow tent, conversation intertwined with scissors and pencils, each sound a thread in their shared fabric of resilience.

When Ki looked at the finished duck, her face brightened. It reminded her of backyard summers in the United States when ducks wandered through the grass. It recalled a giant rubber duck she had once seen in Beijing, a memory buried until the act of making called it back. The duck became allegory. On land it walked, in water it swam, in air it flew. Ki recognized herself in that movement. On land she cooked for many tastes. In water she navigated unfamiliar systems of insurance and school. In air she guarded her children with vigilance.

The duck tent glowed gently beside/outside/inside the larger yellow tent. Its paper body carried more than craft. It carried her daughter’s drawings, her own memories of bias and struggle, her daily exhaustion, her hope. The amulet whispered softly: keep quacking. To quack is to speak, sometimes faintly, sometimes insistently, but always to declare something.

The yellow duck tent was fragile, yet it stood. In its stillness it held motion. In its lightness it held strength. In its small persistent quack it carried a mother’s endurance, a family’s migration, and the quiet vow to remain visible.