In the Middle:

Adoption, Diaspora, and the Making of a Stained-Glass Tent

In a park of drifting seeds and shifting light, Ada lifted her stained glass toward the sun and unfolded a tent of memory. Between China and the United States, between adoption and diaspora, she painted flight upon wood and preserved her daughter’s touch. The stained-glass tent became a vessel of belonging, refracting fragility into strength, and holding her story in luminous suspension.

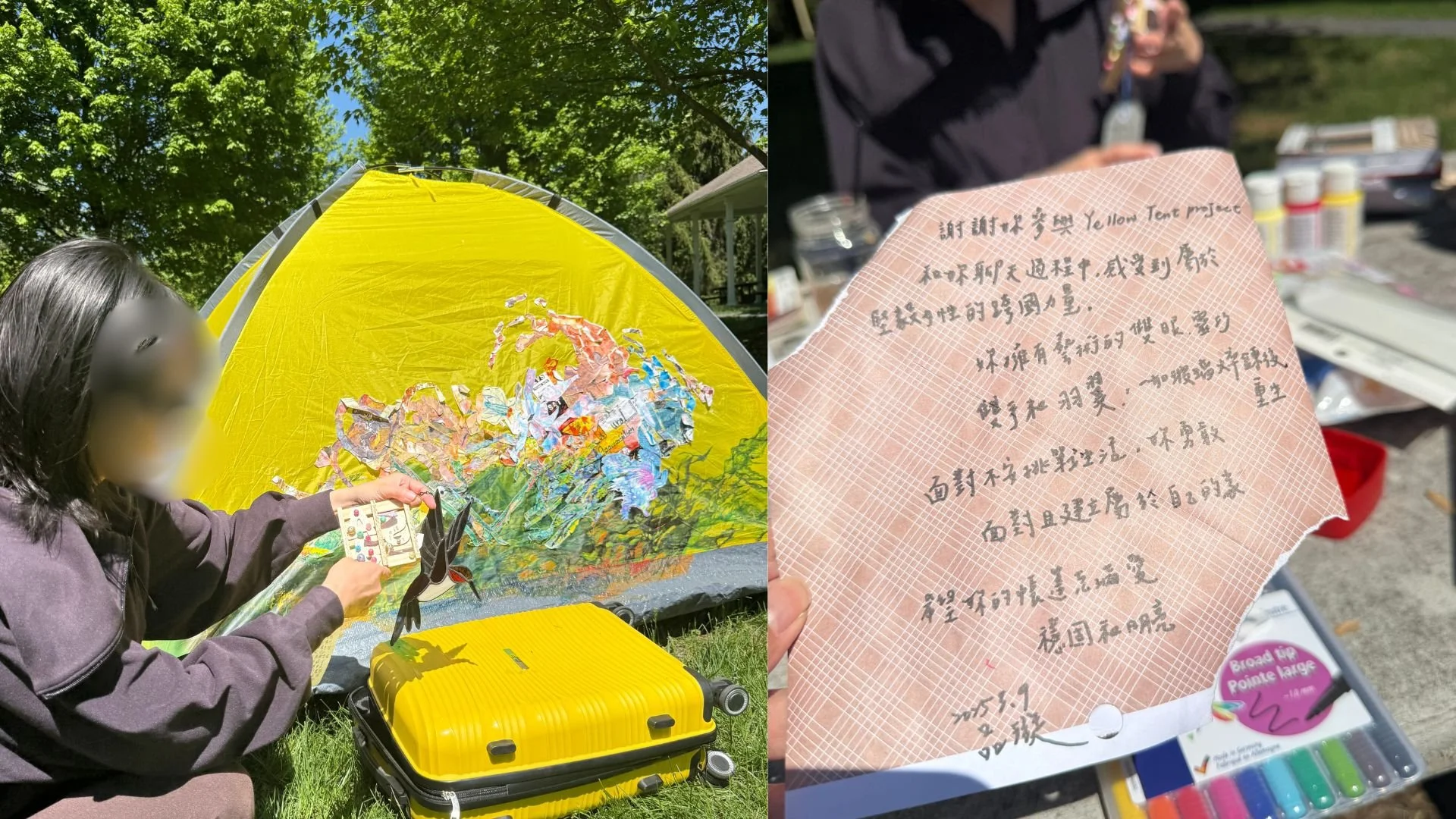

On a warm Saturday afternoon Ada walked into the park carrying two stained glass pieces, shimmering fragments of her week carved out from labor and care. The air was gentle, light scattered through the trees, and winged seeds swirled downward as if to welcome her arrival. She smiled, saying this place was her sanctuary, a space to breathe, to remember herself. I opened my yellow carry on and unfolded the tent. She reached to help, threading poles through fabric, seeds landing on our shoulders and hair. She laughed. “Perhaps your tent will collect more materials after today.”

The tent rose slowly into shape, its yellow cloth quivering in the breeze. Ada lifted her stained glass to the sun, holding it as one holds a secret that longs for release. Light poured through green, blue, and red, spilling across her face and the panels of the tent. “I chose glass because my life is like it,” she whispered. “Fire refines and transforms materials, like me.” In her hands, the molten story of sand and metal, fused by fire into fragile brilliance, became a mirror of her own crossings and transformations.

At thirteen and a half she left China, adopted by a White American Christian family, just before the law would have closed that door forever. She called it a race against time. In America she found, for the first time, what she named a complete family, with parents and sibling and school. Yet the sense of arrival was never simple. In classrooms, voices mocked her with questions about eating dogs. During the pandemic, suspicion turned heavier, and fear shadowed her daily walk. “I am often in the middle,” she reflected, between China and the United States, between the White family who raised her and the Asian community she found through her Taiwanese partner.

Her stained glass tent embodied this in betweenness. On a wooden pallet she traced the shifting colors, painting the red of a bird at the moment of flight. She inscribed three letters on the hidden side of the wood, the initials of her family, tucked away until the pallet was turned. “When we flip the glass, what was invisible becomes visible.” Inside and outside, concealment and revelation, both contained in a single gesture.

Her daughter soon arrived, scattering bright beans across the pallet with the exuberance of play. Ada bent low to preserve the small constellation. “She will be happy to see this later.” Their voices mingled beside the tent. “Mom, are you putting on makeup.” “No, we are creating.” Together they laid purple cloth over the pallet, a sign of protection, and placed a Mandarin amulet for the family. In this layering the tent became home, both fragile and steadfast.

Ada paused and looked around. “I am not a person who studies. This is the first time I have felt how art can bring reflection, and how someone listens so carefully.” Sunlight poured through the stained glass and yellow fabric, filling the tent with warmth. The beans her daughter placed, the winged seeds drifting through air, the hidden names etched in wood, all gathered as fragments of a story told in the middle.

Her tent was not only glass and wood and cloth. It was light and breath, the weight of memory, the presence of her child, the trace of migration. It refracted adoption and diaspora, revealing both loss and resilience. She compared herself to the bird in her glass, its wings trembling with energy. “I am a freedom person,” she said. The tent was more than structure. It was a vessel of belonging, a fragile house of light where transformation could begin.

“I choose the glass because my life is like it, because fire refines and transforms different materials, like me.”

“When a bird takes flight, that moment requires the most strength. Its wings are just beginning, just starting the process of flying.”

“Stained glass, with its capacity to transform light, connected my journey of migration and transformation. When lifted to the sun, it alters colors in the surrounding scene, revealing subtle hues, shifting boundaries, and creating moments of magic. “